The Free Colored People of North Carolina

Southern Workman

March 1902

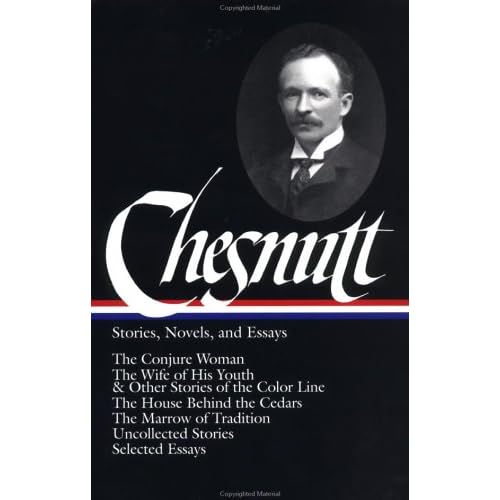

Charles W. Chesnutt

From the Charles Chesnutt Digital Archive. This site maintained by Stephanie Browner.

In our generalizations upon American history—and the American people are prone to loose generalization, especially where the Negro is concerned—it is ordinarily assumed that the entire colored race was set free as the result of the Civil War. While this is true in a broad, moral sense, there was, nevertheless, a very considerable technical exception in the case of several hundred thousand free people of color, a great many of whom were residents of the Southern States. Although the emancipation of their race brought to these a larger measure of liberty than they had previously enjoyed, it did not confer upon them personal freedom, which they possessed already. These free colored people were variously distributed, being most numerous, perhaps, in Maryland, where, in the year 1850, for example, in a state with 87,189 slaves, there were 83,942 free colored people, the white population of the State being 515,918; and perhaps least numerous in Georgia, of all the slave states, where, to a slave population of 462,198, there were only 351 free people of color, or less than three-fourths of one per cent., as against the about fifty per cent. in Maryland. Next to Maryland came Virginia, with 58,042 free colored people, North Carolina with 30,463, Louisiana with 18,647, (of whom 10,939 were in the parish of New Orleans alone), and South Carolina with 9,914. For these statistics, I have of course referred to the census reports for the years mentioned. In the year 1850, according to the same authority, there were in the state of North Carolina 553,028 white people, 288,548 slaves, and 27,463 free colored people. In 1860, the white population of the state was 631,100, slaves 331,059, free colored people, 30,463.

These figures for 1850 and 1860 show that between nine and ten per cent. of the colored population, and about three per cent. of the total population in each of those years, were free colored people, the ratio of increase during the intervening period being inconsiderable. In the decade preceding 1850 the ratio of increase had been somewhat different. From 1840 to 1850 the white population of the state had increased 14.05 per cent., the slave population 17.38 per cent., the free colored population 20.81 per cent. In the long period from 1790 to 1860, during which the total percentage of increase for the whole population of the state was 700.16, that of the whites was 750.30 per cent., that of the free colored people 720.65 per cent., and that of the slave population but 450 per cent., the total increase in free population being 747.56 per cent.

It seems altogether probable that but for the radical change in the character of slavery, following the invention of the cotton-gin and the consequent great demand for laborers upon the far Southern plantations, which turned the border states into breeding-grounds for slaves, the forces of freedom might in time have overcome those of slavery, and the institution might have died a natural death, as it already had in the Northern States, and as it subsequently did in Brazil and Cuba. To these changed industrial conditions was due, in all probability, in the decade following 1850, the stationary ratio of free colored people to slaves against the larger increase from 1840 to 1850. The gradual growth of the slave power had discouraged the manumission of slaves, had resulted in legislation curtailing the rights and privileges of free people of color, and had driven many of these to seek homes in the North and West, in communities where, if not warmly welcomed as citizens, they were at least tolerated as freemen…

…One of these curiously mixed people left his mark upon the history of the state—a bloody mark, too, for the Indian in him did not pass-ively endure the things to which the Negro strain rendered him subject. Henry Berry Lowrey was what was known as a “Scuffletown mu-latto” Scuffletown being a rambling community in Robeson county, N. C., inhabited mainly by people of this origin. His father, a prosperous farmer, was impressed, like other free Negroes, during the Civ-il War, for service upon the Confederate public works. He resisted and was shot to death with several sons who were assisting him. A younger son, Henry Berry Lowrey, swore an oath to avenge the injury, and a few years later carried it out with true Indian persistence and ferocity. During a career of murder and robbery extending over several years, in which he was aided by an organized band of desperadoes who rendezvoused in inaccessible swamps and terrorized the county, he killed every white man concerned in his father’s death, and incidentally several others who interfered with his plans, making in all a total of some thirty killings. A body of romance grew up about this swarthy Robin Hood, who, armed to the teeth, would freely walk into the towns and about the railroad stations, knowing full well that there was a price upon his head, but relying for safety upon the sympathy of the blacks and the fears of the whites. His pretty yellow wife, “Rhody,” was known as “the queen of Scuffletown.” Northern reporters came down to write him up. An astute Boston detective who penetrated, under false colors, to his stronghold, is said to have been put to death with savage tortures. A state official was once conducted, by devious paths, under Lowrey’s safeguard, to the outlaw’s camp, in order that he might see for himself how difficult it would be to dislodge them. A dime novel was founded upon his exploits. The state offered ten thousand, the Federal government, five thousand dollars for his capture, and a regiment of Federal troops was sent to subdue him, his career resembling very much that of the picturesque Italian bandit who has recently been captured after a long career of crime. Lowrey only succumbed in the end to a bullet from the hand of a treacherous comrade, and there is even yet a tradition that he escaped and made his way to a distant state. Some years ago these mixed Indians and Negroes were recognized by the North Carolina legislature as “Croatan Indians,” being supposed to have descended from a tribe of that name and the whites of the lost first white colony of Virginia. They are allowed, among other special privileges conferred by this legislation, to have separate schools of their own, being placed, in certain other respects, upon a plane somewhat above that of the Negroes and a little below that of the whites…

Read the entire essay here.