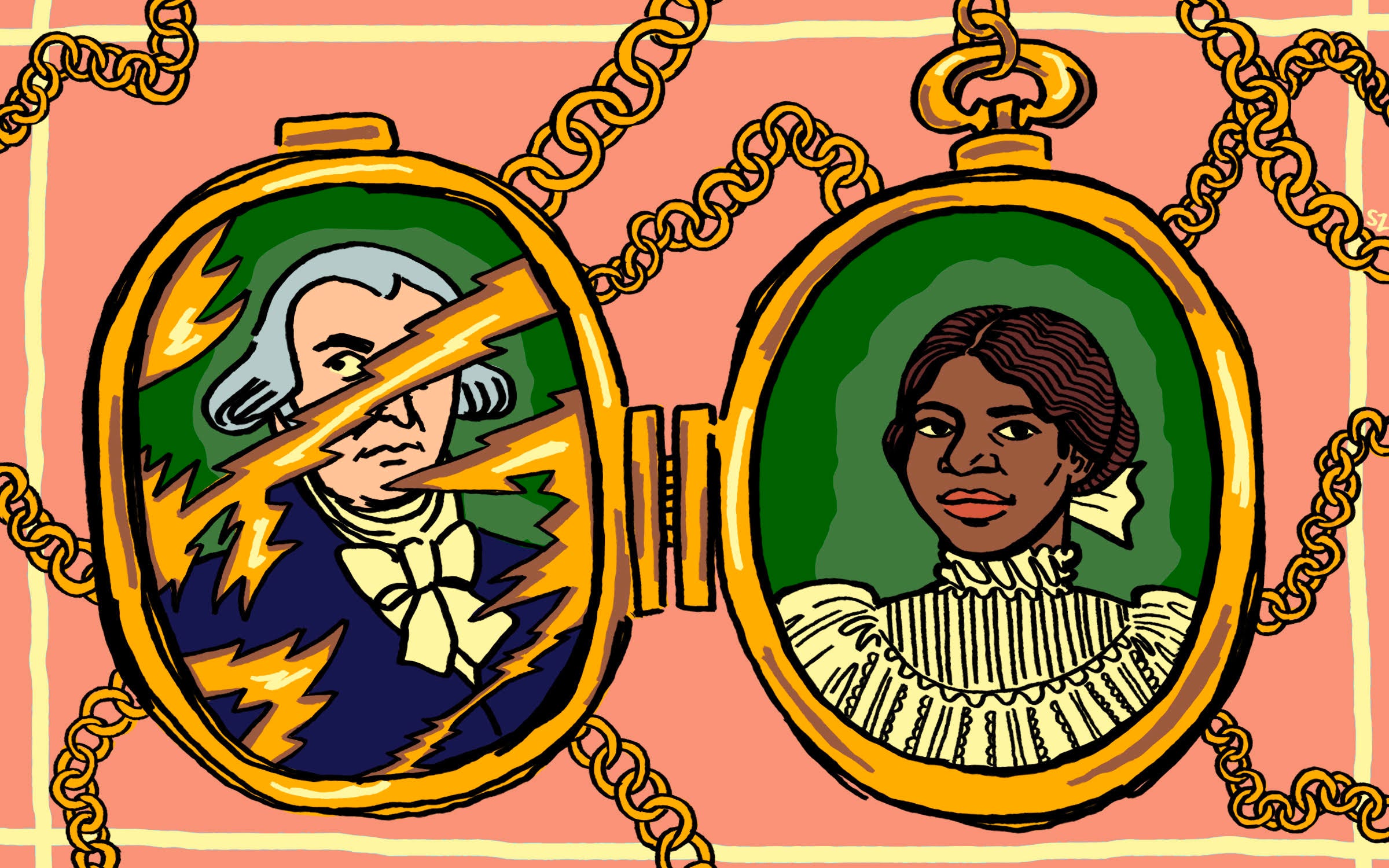

I Am a Descendant of James Madison and His Slave

Illustration: Sophia Zarders

My whole life, my mother told me, ‘Always remember — you’re a Madison. You come from African slaves and a president.’

President Madison did not have children with his wife, Dolley. Leading scholars believe he was impotent, infertile, or both. But the stories I have heard since my childhood say that James Madison, a Founding Father of our nation, was also a founding father of my African American family.

In my childhood, whenever I whined or squirmed or got into trouble, my mother repeated the refrain: “Always remember — you’re a Madison. You come from African slaves and a president.” This is my family’s credo, the statement that has guided us for 200 years.

Though many in our family have heard we descend from President Madison and his slaves, only the griots — the one-in-a-generation oral historians in the family — know the full account of our ancestors, White and Black, in America. Gramps had told me many stories, but the detailed family history was Mom’s responsibility to convey to me when I became the next griotte.

The night my mother passed those stories on to me, I understood for the first time why some of the details of our family history were passed only from the griot of one generation to that of the next. Not only were some of the stories intimate, but this tradition safeguarded their accuracy, truth, and longevity. I sank into the sofa with my mother and listened with a new awareness of the significance of her words and what they meant to me. She began…

Read the entire article here.