Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire by Akala – review

The Guardian

2018-05-20

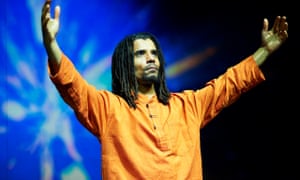

Akala: ‘a disruptive, aggressive intellect’. Photograph: Rob Baker Ashton/BBC/Green Acre Films |

In a powerful, polemical narrative, the rapper charts his past and the history of black Britain

In 2010, UK rap artist Akala dropped the album DoubleThink, and with it, some unforgettable words. “First time I saw knives penetrate flesh, it was meat cleavers to the back of the head,” the north London rapper remembers of his childhood. Like so much of his work, the song Find No Enemy blends his life in the struggle of poverty, race, class and violence, with the search for answers. “Apparently,” it continues, “I’m second-generation black Caribbean. And half white Scottish. Whatever that means.”

Any of the million-plus people who have since followed Akala – real name Kingslee Daley – know that the search has taken him into the realm of serious scholarship. He is now known as much for his political analysis as for his music, and, unsurprisingly, his new book, Natives, is therefore long awaited. What was that meat cleaver incident? What was his relationship with his family and peers like growing up? How did he make the journey from geeky child, to sullen and armed teenager, to writer, artist and intellectual?.

Natives delivers the answers, and some of them are hard to hear. In one of the most touching of many personal passages in the book, Akala retraces the steps by which he was racialised – as a mixed-race child – into blackness, and by which he realised that his mother, who fiercely protected her children’s pride in their heritage, enrolling them among other things in a Pan-African Saturday school, was racialised as white…

Read the entire article here.