Jolene Ivey on The Rock Newman Show

The Rock Newman Show

Busboys and Poets

Washington, D.C.

2013-10-19

Rock Newman, Host

Jolene Ivey, Representative, 47th District, Maryland House of Delegates

Also candidate for Maryland Lieutenant Governor

Maryland’s House of Delegates member and 2014 Maryland gubernatorial Running Mate, Jolene Ivey visits The Rock Newman Show. Delegate Jolene Ivey talks about growing up in Maryland, her family, issues in the state of Maryland and her political career. Including the campaign that could make her the first female African American lieutenant governor in Maryland’s history.

Partial transcription by Steven F. Riley

00:09:48 Rock Newman: In the spirit of my audience, understanding who you are. Let’s go back. Let’s go all the way back. I’d like to know where you where born, where you grew up, where you went to elementary school. Let’s start with those three things. Let’s go all the way back.

Jolene Ivey: Oh boy. My dad was in the military, actually he was a Buffalo Soldier.

RN: Okay.

JI: So he was in World War II and the Korean War, so 20 years. Then he became a public school teacher in Prince George’s County public schools for the next 20 years.

RN: Oh wow. Where did he teach?

JI: He taught at Douglas in south county and then he taught at High Point, which was my alma mater in Beltsville.

RN: Okay.

JI: So he taught at Douglas when we had segregation, of course all the black kids, all the black teachers were there.

RN: Sure.

JI: And then when they desegregated, they sent a few black teachers to other schools. That’s when he got moved to High Point.

RN: Okay.

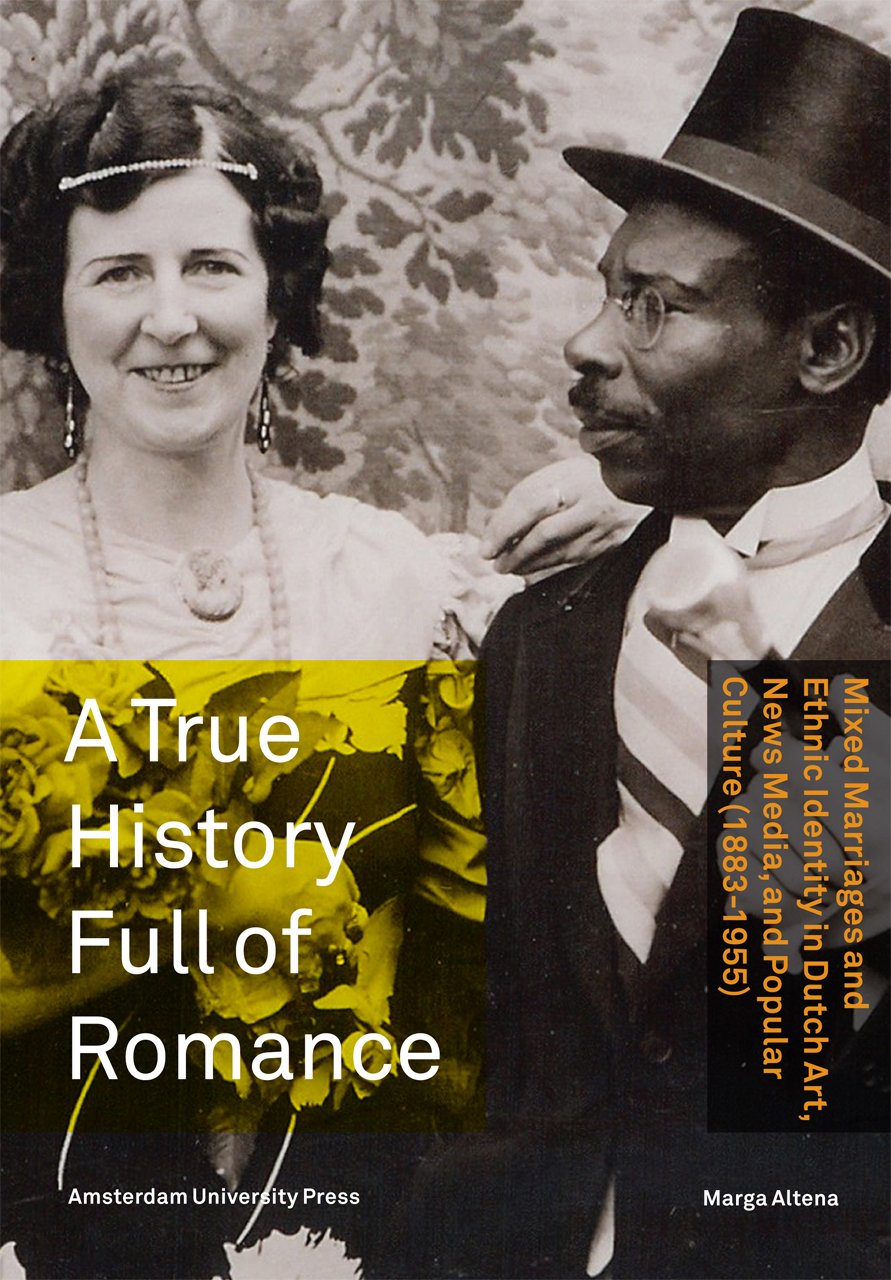

JI: Yeah. But in any event, he and my mom were married in the fifties. Now, my mom is white..

RN: Uh uh.

JI: …and my dad’s black.

RN: Right.

JI: And it was illegal at that time for them to be married in Maryland… or Virginia. So in this area, they had to live in D.C. [Be]cause D.C. was the one place they could be legally wed. So we lived in Northeast D.C., lived on…

RN: Let me just stop you there. [Be]cause you know, I try to take those moments for my audience. You know, that stuff doesn’t just float by. It’s like, wow, wait a minute. There’re certain posts we can latch on to. Did you hear what she said? In the fifties, as early back as the fifties!

JI: In fact it was the sixties and it was still illegal.

RN: Still illegal..

JI: I think it was… [19]66 before the law changed.

RN: Maryland and Virginia, so they actually,… for them to be married and to reside in Maryland and Virginia your mom and dad. Dad who’s black and the mother’s who’s white, they had to live in the District of Columbia.

JI: They didn’t have any choice. Because you know, the Lovings, the couple that changed the law the whole country, they were in Virginia…

RN: Right.

JI: …when they got married. And they got in a whole heap of trouble.

RN: Right.

JI: And it ended up being a Supreme Court case.

RN: Yes.

JI: Fortunately we won the case. The right side won.

RN: Right.

JI: But, my parents and us, lived in Northeast D.C. in Riggs Park.

RN: Okay.

JI: My mom left when I was three. And my dad raised us. He told her you can do whatever you want, but the kids stay with me. So dad was just an outstanding father. And he raised me and my brother. Um, my stepmother joined us when I was about seven. And you know.

RN: Where did you go to elementary school?

JI: I went to LaSalle Elementary right there in Riggs Park and it was kind of tough on me then boy… middle school, Bertie Backus Middle School. I loved the school, but I had some bad memories from part of it.

RN: And what are the bad memories?

JI: Well, you know what it’s like Rock. You grow up in an all-black neighborhood and especially back then as light I am. I was getting my butt whipped! I mean, and I was real skinny too.

RN: A little tiny thing.

JI: A little tiny thing! Getting picked on. But anyway, it made me tough. And by the time I went to high school, I ended going to high school the same school my dad taught at. So year—which is High Point High School—the first year we still lived in D.C., so we had to pay for me to go the first year, [be]cause it was out of the region. But after that we moved to Prince George’s county and I was able to just continue to go to High Point…

…00:21:36

Rock Newman: Jolene, before we went to break, we got a little biographical information about you. And we left off where obviously there was the incredible strong influence of your father, your grandmother you said was an influence also and you said she brought some joy in your life.

What I was wondering, did you have a particular idol outside of your father and grandmother, a teacher, a public figure, whatever, that might have been… who had an impact on your life early on?

Jolene Ivey: You know, it’s gonna sound corny, okay, but it was Martin Luther King. And…

RN: That doesn’t sound corny at all… [Be]cause we all have a dream.

JI: Right, Right. And you know, he was such a point of discussion in my family. And when he was killed, there was a television, a local television [that] came to our school to interview kids about how they felt..

RN: This was now maybe when you were in Junior High?

JI: No, No.

RN: Elementary.

JI: At the time it happened, I was just a little kid and I remember this local television came out to interview kids about what was his impact on our lives. And I know that when they saw me sitting in that class, they were like, “what the heck is this little ‘white-looking’ girl doing in this class,” but they interviewed me and I came home and I told my parents, told my family, “I’m going to be on television tonight.” And they were like, “Yeah, you don’t know what you’re talking about!” And so, when it was time for it to come on, I went and turned on the TV and they were like “What’s she watching?” And they came, and sure enough, there I was. And they asked me what his impact had been on me and I said, “he got us a seat on the bus.”

RN: Go on now!…