Blackness and Whiteness

Our Human Family: Conversations on achieving equality

2019-05-07

Emily Cashour

Oakland, California

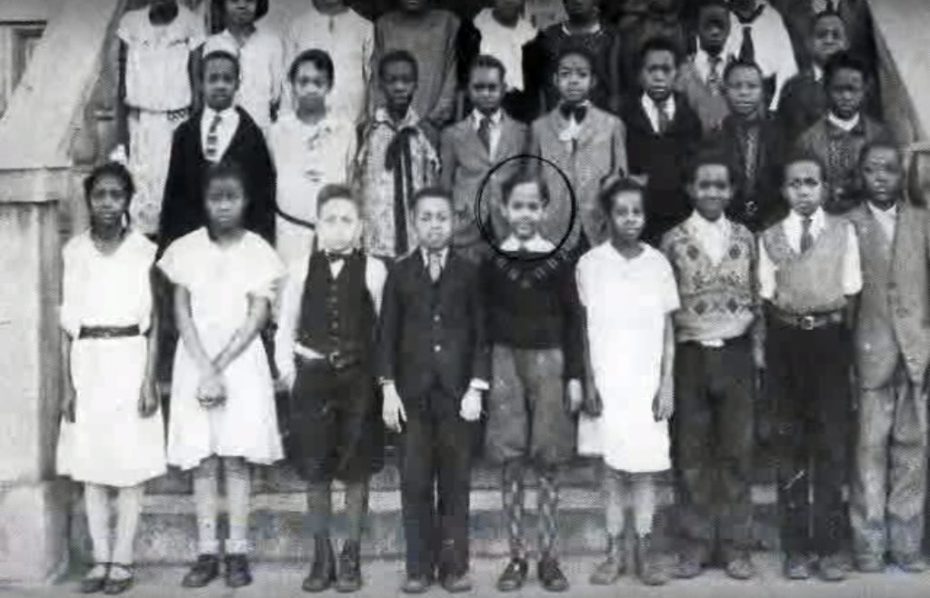

The author and her mother

Growing up as mixed-race alongside my white mother

Growing up, I was unaccustomed to discussions about race. For most of my life, the color of my skin was something simple, a fact that became more or less apparent alongside the changing seasons. When it started to become impossible to ignore, as a young child, I pushed to downplay my color difference. I sat in the shade with my white cousins at the beach to prevent the sun from reaching me, complained with a gentle fierceness each time my mother took me to get my hair braided, said quiet “thank-yous” with no further explanation to people who gleefully oohed and ahhed at my beautiful tan.

As a teenager, I embraced wholeheartedly the idea of tan equaling beautiful, at least so far as in the context of tan being simply a new shade of whiteness, rather than brownness. I was a tan white person. At least, that is what everyone in my town assumed me to be, and rather than fight the simplicity of that label, I allowed it to begin defining me.

My mom, a white woman and single mother, was quiet during these years. If I had questions, she would answer them willingly, but quite honestly, I rarely ever asked her anything. Sometimes, when she took me to Baltimore, we drove home the long way, observing dilapidated neighborhoods and houses with wooden boards with holes in them where windows should’ve been. The sidewalks and the weeds in the place of gardens made these communities look tired, winded. It was clear that places like this were worlds away from where my mom and I lived; yet we were both keen outsiders, desperate for a deeper understanding. There’s something funny about an obviously white woman and an obviously brown child alone together, trying to find a community. On those trips to Baltimore, my mother and I had not quite identified our community yet…

Read the entire article here.