Queer Memory and Black Germans

The New Fascism Syllabus: Exploring the New Right through Scholarship and Civic Engagement

2021-06-08

Tiffany N. Florvil, Associate Professor of European History

University of New Mexico

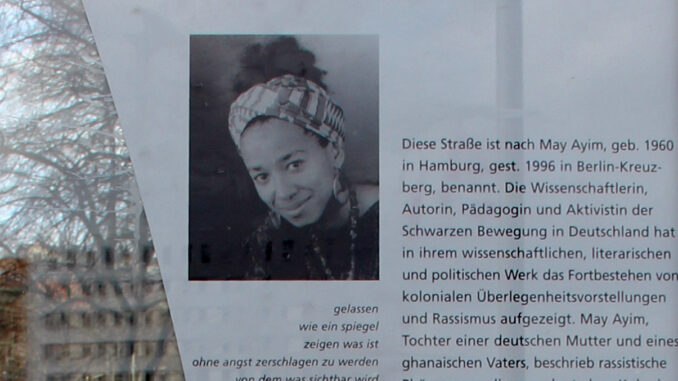

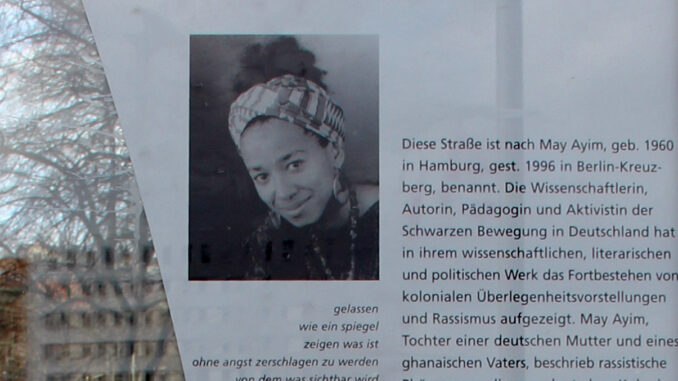

Memorial plaque, May-Ayim-Ufer, Berlin. OTFW CC BY-SA 3.0. |

In “The German Catechism,” Dirk Moses offers an interesting intervention by challenging the idea of the Holocaust’s uniqueness as well as current debates about the Holocaust and its connection to German colonialism, especially the Namibian genocide (1904-08). He also addresses the stifled debates surrounding antisemitism, Israel, and Palestine. In making his argument, Moses uses five points to explore Germans’ abilities to come to terms with their genocidal past and how that past has shaped subsequent postwar efforts at state (re)building, national identity, belonging, and restitution. Postcolonial scholars such as Paul Gilroy, Frantz Fanon, and Aimé Césaire have long acknowledged the interconnections among colonialism, antisemitism, racism, and the Holocaust. Moses even references the latter two theorists in his piece. I applaud some of his intellectual provocations as well as the other contributors in this exciting forum (i.e. Frank Biess, Alon Confino, Bill Niven, Zoe Samudzi, Helmut Walser Smith, Johannes von Moltke, etc.). Together, they not only force us to grapple with these histories and our own positionalities, but they affirm how subjective (and not value-free) the production and dissemination of knowledge really is.

As much as I welcome debate, I am left pondering what is exactly new about Moses’s claims given that Black (queer) women in Germany examined the Holocaust and memory politics since the 1980s often outside of academic institutions and mainstream debates; sadly, a dynamic that is still common today. There were (and remain) racialized communities in Germany who used the Holocaust as a point of reference for opening up public dialogues about discrimination and systemic racism. They did so in their community and in their own publications, constructing a new public sphere. This was not taken up in the mainstream; it still isn’t today. Where are the voices of those individuals in these German debates past and present? This is also striking considering that those same communities demonstrated in their cultural and political work how “Memories are not owned by groups—nor are groups owned by memories. Rather, the borders of memory and identity are jagged”—a point stressed in Michael Rothberg’s Multidirectional Memory (2009), which is encountering criticism in today’s Germany, but which has propelled analysis of the complex, overlapping layers of memory at play in the postwar years. If Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung is such a fundamental feature of postwar German society, where are the perspectives from Black German, Turkish German, and Romani communities? Why don’t we know them and why aren’t they shaping the debate? The latter group was not officially recognized as victims of the Third Reich until 1982. It is the first group I will focus on in further detail below…

Read the entire article here.