Declared Defective: Native Americans, Eugenics, and the Myth of Nam HollowPosted in Anthropology, Books, History, Media Archive, Monographs, Tri-Racial Isolates, United States on 2018-05-27 23:50Z by Steven |

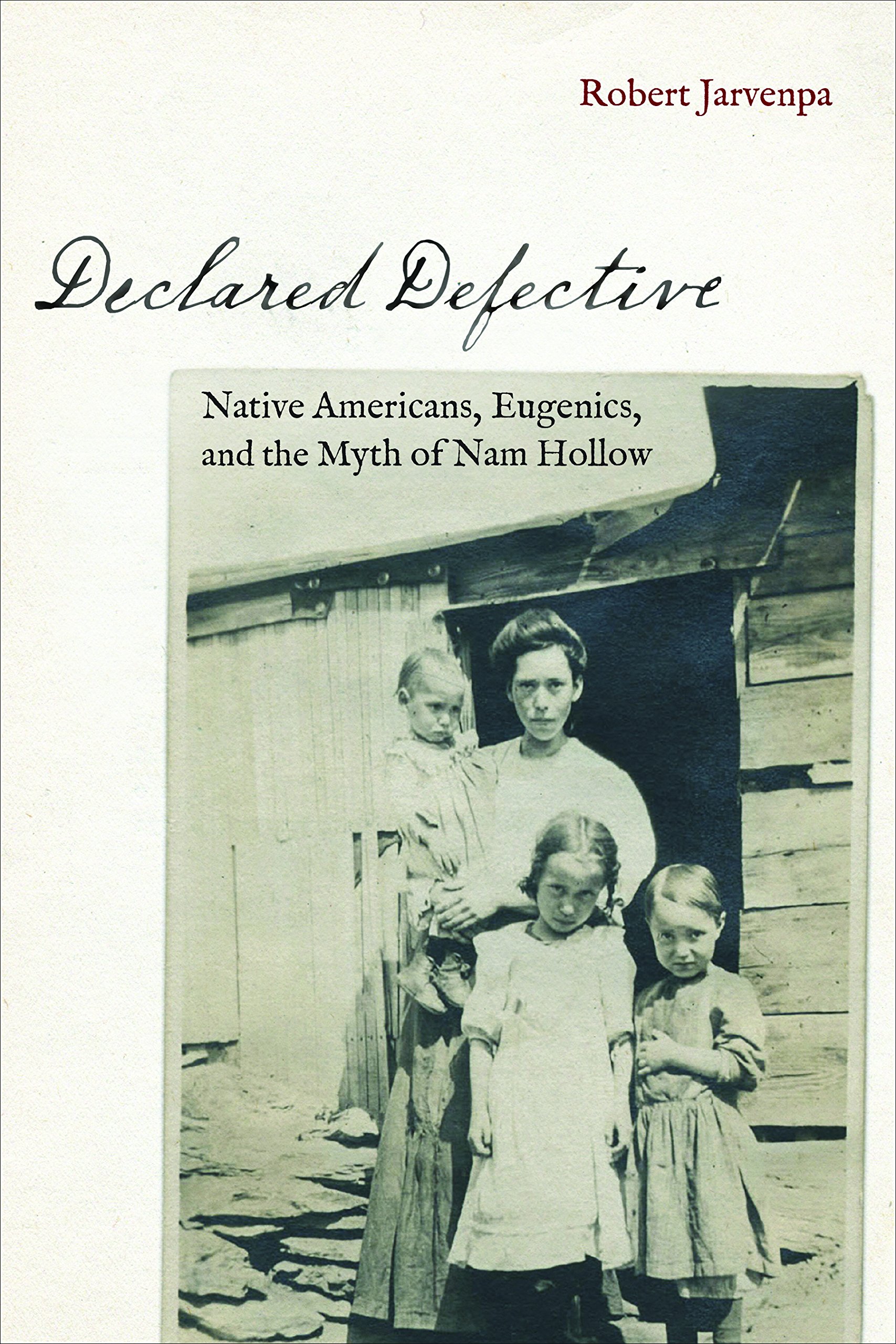

Declared Defective: Native Americans, Eugenics, and the Myth of Nam Hollow

University of Nebraska Press

May 2018

246 pages

9 photographs, 1 illustration, 3 maps, 2 tables, 8 charts, index

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-4962-0200-0

Robert Jarvenpa, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology

State University of New York, Albany

Declared Defective is the anthropological history of an outcast community and a critical reevaluation of The Nam Family, written in 1912 by Arthur Estabrook and Charles Davenport, leaders of the early twentieth-century eugenics movement. Based on their investigations of an obscure rural enclave in upstate New York, the biologists were repulsed by the poverty and behavior of the people in Nam Hollow. They claimed that their alleged indolence, feeble-mindedness, licentiousness, alcoholism, and criminality were biologically inherited.

Declared Defective reveals that Nam Hollow was actually a community of marginalized, mixed-race Native Americans, the Van Guilders, adapting to scarce resources during an era of tumultuous political and economic change. Their Mohican ancestors had lost lands and been displaced from the frontiers of colonial expansion in western Massachusetts in the late eighteenth century. Estabrook and Davenport’s portrait of innate degeneracy was a grotesque mischaracterization based on class prejudice and ignorance of the history and hybridic subculture of the people of Guilder Hollow. By bringing historical experience, agency, and cultural process to the forefront of analysis, Declared Defective illuminates the real lives and struggles of the Mohican Van Guilders. It also exposes the pseudoscientific zealotry and fearmongering of Progressive Era eugenics while exploring the contradictions of race and class in America.

Table of Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Tables

- Series Editors’ Introduction

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Menace in the Hollow

- 1. Native Americans and Eugenics

- 2. Border Wars and the Origins of the Van Guilders

- 3. A “New” Homeland and the Cradle of Guilder Hollow

- 4. From Pioneers to Outcastes

- 5. The Eugenicists Arrive

- 6. Deconstructing the Nam and the Hidden Native Americans

- 7. Demonizing the Marginalized Poor

- Conclusion: The Myth Unravels

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index