‘Do you ever think about me?’: the children sex tourists leave behind

The Guardian

2019-03-02

Margaret Simons, Associate Professor of Journalism

Monash University, Melbourne, Australia

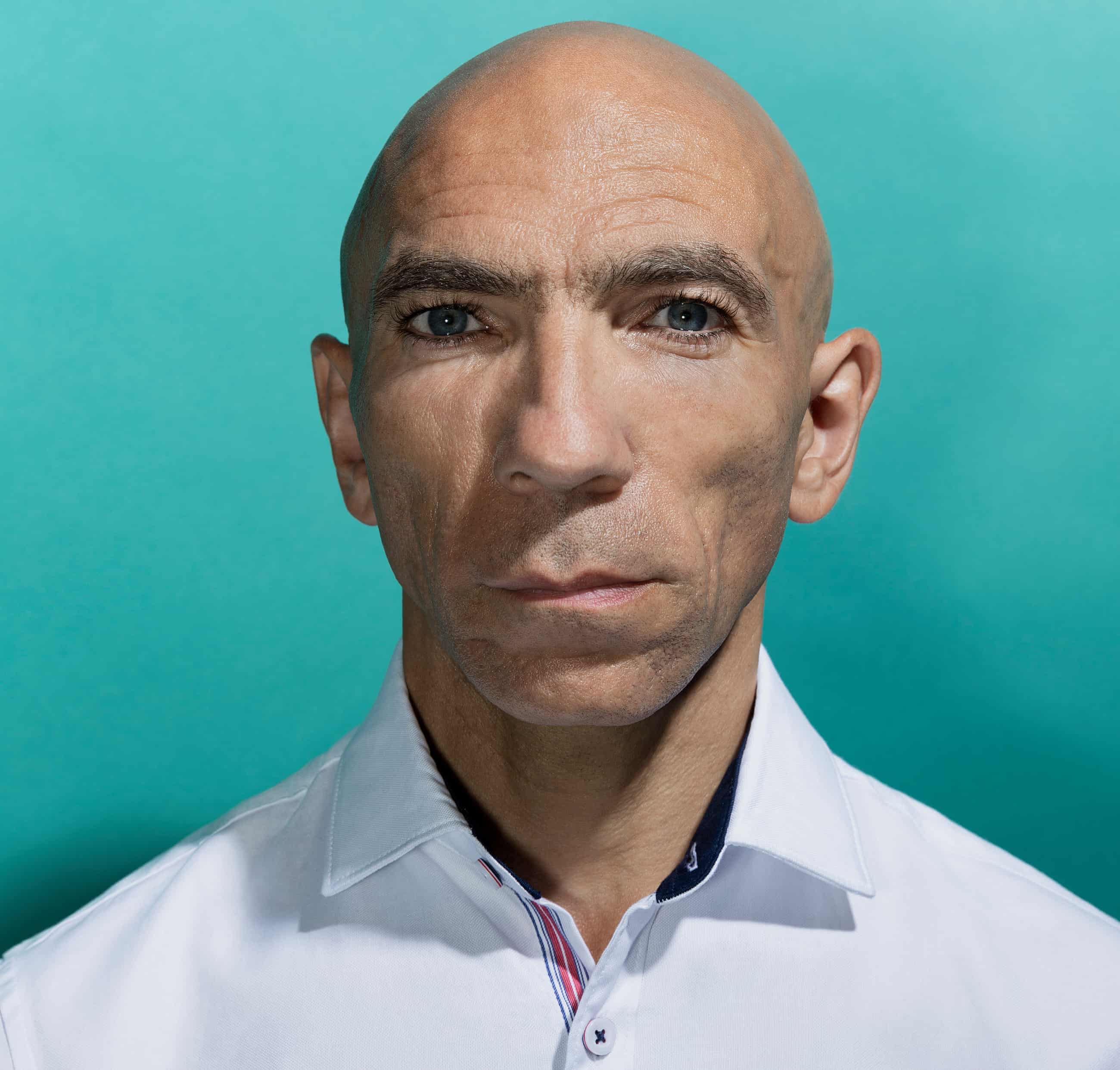

Brigette Sicat knows that somewhere, far away, in a barely imaginable place called England, she has a father. Photograph: Dave Tacon |

Their fathers visited the Philippines to buy sex: now a generation of children want to track them down

Brigette Sicat will not be going to school today. She sits, knees to chest, in a faded Winnie-the-Pooh T-shirt, on the double mattress that makes up half her home. At night, she curls up here with her grandmother and two cousins, beneath the leaky sheets of corrugated iron that pass for a roof. Today, the monsoon rain is constant and the floor has turned to mud.

Brigette, 10, and her 11-year-old cousin, Arianne, aren’t in school because they have a stomach bug. There is no toilet and no running water, and no means of cooking other than over an open fire. Even when she is well, Brigette is often too hungry to tackle the 10-minute walk to school. Brigette’s mother is a sex worker. And Brigette knows that somewhere, far away, in a barely imaginable but often-thought-of place called England, she has a father. She knows only his given name: Matthew.

Asked what she would say to him, were she able to send him a message, Brigette is at first stumped for words. Then she bursts out in Tagalog: “Who are you? Where are you? Do you ever think about me?” Her grandmother, Juana, her fingers swollen with arthritis and suffering from a lack of medication for her diabetes, sits by her side.

Juana, Arianne, Brigette and Arianne’s brother, Aris, survive on 200 pesos (£3) a day, contributed by Arianne and Aris’s father. (He drives a Jeepney – a public transport vehicle originally converted from Jeeps abandoned by the US military.) Juana, 61, tells me she thinks she may not live much longer. But she wants the girls to finish school, to keep them from working in the bars.

These are the slums of Angeles City in the Philippines, and the children here represent a United Nations of parentage. Their faces tell that story – fair skin, black skin, Korean features, caucasian. That’s because their fathers, like Brigette’s, are sex tourists…

Read the entire article here.